Part 2 of the post To Feather the Shock

We turned a corner, and on a flat stretch where the wind blew the clouds apart, the light entered the floor of the forest. There we spotted a few small quetzal feathers shining against the fallen leaves. A glimmer, alongside some shining fluff on the ground, indicated that a quetzal had been killed. Was it a bird of prey that had spotted the quetzal? Or a hunter? This death was as mysterious as the survival of these elusive birds, who rely on the seasonal abundance of the forest’s fruits to stay alive.[i]

The scattered feathers were the remaining traces of an almost extinct bird. Delicate, tuned in to its environment, it lives in symbiosis with the plants who need this particular bird to complete their lifecycle; without the quetzal, the wild avocado will also die out.

Who had caught the quetzal? Who had then taken it away? Its body was not there. We searched through the undergrowth, so dense that finding a bird’s body not lying directly on the path—kept clear by rangers with machetes—seemed hopeless. Only the few feathers from the body and one slightly longer green one, freshly fallen and hard to see among the vegetation, remained on the path.

The color of the quetzal made sense now. Dark black and green, shimmering, like water on leaves that shines when the light breaks through the clouds. A kind of glowing green—but only at certain moments. Not a constant, but something that comes with light, something otherwise dark. Resplendent when the light hits it. A bit like the Greek idea of truth, Alethia—the moment when light hits the Lethe, the river of oblivion, negating the loss of memory. We were in a kind of river of oblivion with our small sufferings along the trail. Only on occasions were there windows that opened—pockets of light on the tangle of vines.

Seven in the morning and we are deep in the forest listening for birds. The narco-traffickers circle above in light aircraft. “No other plane takes this route,” the guide, biologist, and birder Alberto Martinez, says. Different worlds collide. The quetzal’s breeding season is over. But I see the woodpecker’s roosting places, which the quetzals will recycle into nests for themselves. They never entirely build their own nests, but they are very picky about where they live, and El Triunfo, a biosphere reserve in Chiapas, Mexico, is one of the very few places where they still do.

Quetzal: last known address. Occasionally, we could hear them but not see them. One thing was clear—if they didn’t want to be found, they were not going to be. Being here confirmed my hunch that they were the ones that evolved to look like the forest, to be like the clouds. They were the ones that embodied the cloud forests: dense, immense, and magnificent.

Forest and bird evolved together, mirroring each other.

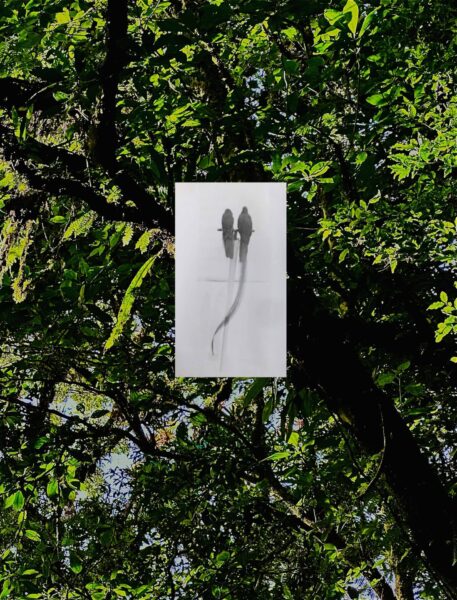

Archival photograph of two quetzals in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, collaged onto a photograph of El Triunfo by the author, 2024.

When I saw the leaf to the left of the pair of archival quetzals in the picture above, I thought I recognized the natural detail the male bird was copying—surely it grew its tail in imitation of this fern. Aztec mythology has a different explanation. The Aztec amanteca (featherworkers) used quetzal feathers to design feather headdresses that moved like snakes. What did the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl have to do with forests? The vipers that are also abundant in El Triunfo remained even more invisible than the quetzal, a silent presence, more silent even than the fern in the wind.

Too Loud a Solitude

We would hear quetzals calling to us, or calling to each other. The guide Alberto would mimic the birds, and the birds would not know who was human. At least that’s what we thought. Then again, they probably knew but were curious anyway. Yet, the only time they came to us singing was when my four-year-old son made a very loose interpretation of them. Everyone laughed at him, including the quetzales.

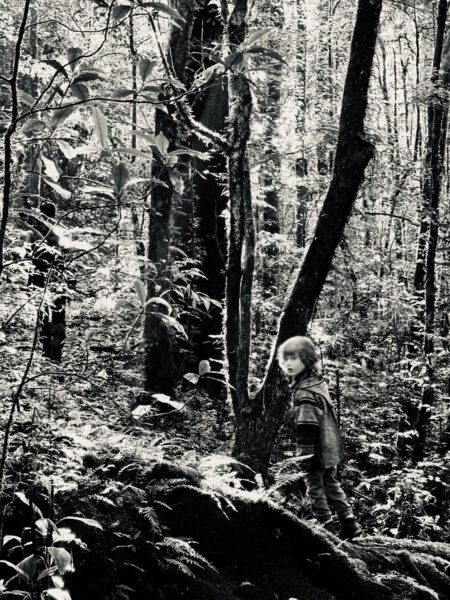

Calling the birds, photo by the author, 2024.

We could mimic their songs, we could pick their avocados, but the laughter would only last so long.[ii] In captivity, they would realize these were not their fresh avocados. The rebreeding program struggled to find food they liked and was feeding them eggs on the morning we visited, which seemed a Saturnian move: making birds eat eggs.

The attempt to imitate quetzales, to be like them, has a long history in Central Mexico. The Aztec priests recognized something of the bird’s power to call from a place where “anything is possible,” as Alberto says when we enter the jungle. It had the ability to enchant and dazzle, but also to withhold and remain mysterious.

Humans mistake the delicacy of the quetzal feather for fragility. But that is not its sensitivity; it is sensitive to an environment, to the wind, and the liquid in the air. It is sensitive to a whole set of relations—to the freshness of fruit, for instance. This bird is famous for refusing to thrive in captivity. When I interview the local communities, many say the quetzal symbolizes libertad—freedom—because it would rather die than dwell under human control.

The quetzal, like many birds, is monogamous; during our stay we often heard the myth that it takes only one mate for life. In fact, we don’t know much about the quetzal’s breeding habits because they have not been studied. Experiments and DNA profiles to measure paternity would help explain why the resplendent quetzal is the only trogon with such striking male ornaments. It is likely that the long tail coverts are for display, given that only the males have them. However, why male ornaments should be so elaborate in a supposedly monogamous species—both male and female cooperate as a pair to raise the young—is a puzzle. My ornithologist friend, Nick Davies at the University of Cambridge, suggests that perhaps males are using them to attract other females for “extra–pair matings.”

To help me solve the riddle of the long tail feathers, Nick offers the advice: “Imagine that you are the animal and it will help you understand the decisions they make.” Why would one bird develop this kind of plumage while all the other birds remain short-tailed in comparison? Why do we not see an endless evolution until the tail feather of every bird hangs like a vine, a balloon string, a cirrus cloud?

Biology tries to answer these questions in rational terms: There must be a reason for the bird doing this. It can’t be for camouflage, because birds develop feathers for attraction—called display—for the purpose of attracting mates. Art history tells us that there is symbolism in ornament and display that is not biologically driven; the reason artists make certain ornaments cannot be reduced to sexual drives. I wonder if it makes sense to also release the quetzal from such determinism? This is not what the locals tell us—the birds are monogamous in their myths, and hence, if one dies, it is irreplaceable. This would mean monogamy and extinction go hand in hand. But that’s not true, the scientists say.

What is true, is the coming, and now the going. Flashes of color. Fireflies at night appear like spirits and disappear like ghosts. Butterflies blow in the cloud forest’s wind like seeds. But the quetzal has disappeared.

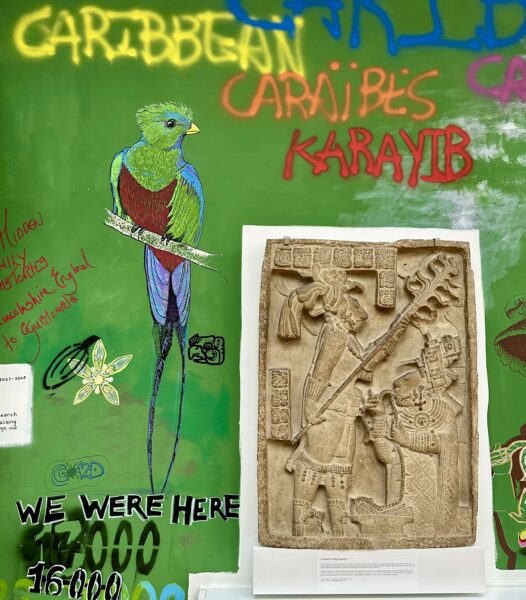

People & Stuff: A Subversive Collaboration, 2025. Site-specific intervention into the Andrews Gallery, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge by Alana Jelinek. Photo by the author.[iii]

I want to look at artists’ gestures of return as direct responses to extraction of materials such as quetzal feathers and patrimony such as the Penacho. That’s what brings me to El Triunfo in the Mexican state of Chiapas. I am here with the artist Nina Hoechtl, and we’re also visiting Zoomat, the zoo in Tuxtla Gutiérrez—the state capital—where environmentalists are trying in vain to rebreed the nearly extinct quetzal. The night before our visit to the zoo, we sit in the city square and talk about this. We discuss Nina’s endeavor to develop a decision-support framework for a sustainability app in cooperation with the National Laboratory of Sustainability Sciences at UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México). As part of this project, she is creating a sustainable souvenir, sales of which would support communities that live around the biosphere, and in turn, support the quetzal.[iv]

It is complex to identify such communities within the villages, as the organizations contracted to manage an area often change. The El Triunfo reserve used to be run by the Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP), but recently another part of the Santa Rita village has received the contract to oversee it. This newly appointed group arrives with us for the first time at the top of the mountain in El Triunfo in August 2024. They have no knowledge of the environment, says Alberto, nor of the methods for maintaining the biosphere research station or supporting the scientists working there. Although the station has a dormitory which can house twenty people at once, a maximum number of two hundred people a year are permitted into the biosphere. Since the biosphere was closed for years during the COVID-19 pandemic, much of the conservation work was disrupted. Alberto is worried about the situation; the contract has not been transferred to these villagers in a way that makes it easy for them to continue the work.

On top of worrying about the narco-traffickers flying overhead dropping drugs near us, Alberto is concerned about this next generation’s prior fears of going into the forest. People used to live entirely in the highlands without interference until the 1980s; the area was a good hide-out from the political unrest playing out below. The cloud forest is a natural boundary, lush and abundant, with its own fortification of trees; one can understand why the Zapatistas—an Indigenous, anti-extractivist, land movement—base themselves in the Chiapas highlands as a retreat where they can gather strength. Our mules, who have the most experience of climbing the route to the summit, stay instinctively close to the research station. At dawn, we glimpse a mountain lion at the edge of the clearing.

This excerpt from an article will be published in the book “Arts and Extractivism in the Global Present,” edited by Liliana Gómez and Alexander Brust and published by Routledge in the series Advances in Art and Visual Studies.

[i] We were in one of the only four regions where quetzals still live—NAME REGION. El Triunfo in Chiapas, Mexico, is the most famously biodiverse ecosystem in which quetzals thrive. SEMARNAT, 2018. Programa de Acción para la Conservación de la Especie Quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno mocinno) (Mexico: SEMARNAT/CONANP, 2018).

[ii] Nidesh Lawtoo, Homo Mimeticus: A New Theory of Imitation (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2022).

[iii] Jimena Lobo Guerrero Arenas, Alana Jelinek and Sarah-Jane Harknett, “Grafiti en el museo: multivocalidad e inclusión a través del arte,” El Futuro del Pasado 16 (2025) forthcoming, https://doi.org/10.14201/fdp.31826

[iv] The app Huella Ecológica was developed by Nina Hoechtl, Yosune Miquelajauregui, Raúl de la Rosa, and Camila Toledo Jaime at the National Laboratory of Sustainability Science at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, accessed May 21, 2025, https://eco-footprint.vercel.app/.