by Nina Hoechtl and Yosune Miquelajauregui

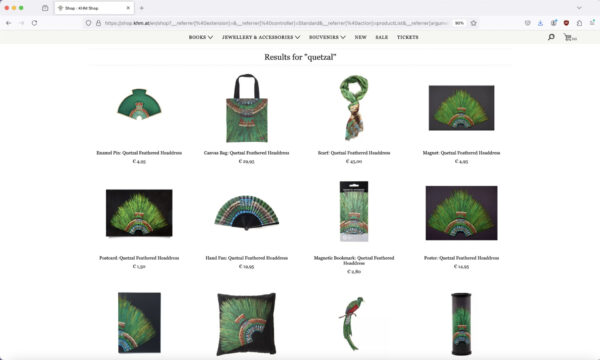

If you visit the website of the shop affiliated with the Weltmuseum, part of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, you will currently find twenty-two souvenirs featuring or relating to one of the most controversial cultural objects in the museum’s collection—the commonly known Penacho de Moctezuma.[1] While in Nahuatl it is called quetzalapanecáyotl, on the website and some of the souvenirs, it is announced as “Quetzal feathered headdress”. You can find these souvenirs under diverse categories, such as “Welmuseum”, “Aztec”, “Feather”, “Quetzal”, in a price range from EUR 1 to EUR 70. Some come with short descriptions.

For instance, on the enamel pin, you can read:

“Size: 34 x 24 mm

enamel covered with epoxy resin

Decorate your jacket or bag with this colorful pin, which is inspired by a very special object from the collection of the Weltmuseum Wien. The magnificient [sic], Aztec Quetzal feathered headdress is the only existing one and consist [sic] of hundreds of long Quetzal-feathers and more than thousand golden ornaments. Quetzal feathered headdress, Mexico, Aztec, early 16th cent., inv. no. 10.402” [2]

Souvenirs are known for being produced in one location—although most of the aforementioned items do not specify their place of production—but are intended for widespread distribution elsewhere. In this case, the souvenirs are premeditated for the region where the quetzalapanecáyotl disappeared under Spanish colonial rule in what is now Mexico. If not bought online, today these souvenirs can be purchased in another cultural site, where the object under question later surfaced in 1596, a territory now known as Austria. In the shop, the quetzalapanecáyotl appears in various sizes, including as jewellery, a scarf, a bag, a fan, or a puzzle. These items can be purchased and taken home, either to be self-gifted or given as a gift to someone else, much like any other souvenir. Souvenirs serve as reminders of past events or distant experiences, carrying their significance into the future. However, the past events that these souvenirs evoke—dating back to Spanish colonization—are far from cheerful and their significance into the future is ripe with contradictions.

It is because of colonial imperial relations and operations that the quetzalapanecáyotl ended up in the collection of the Weltmuseum. Since the beginning of the 19th century, it has been part of the Museum’s collection and over the last 40 years it has faced conflicting desires, divergent interpretations, ongoing discussions, and intensifying demands for restitution. A joint research and restoration project from 2010 to 2012 between the INAH (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History), the UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, National Autonomous University of Mexico) and the Welmuseum came to the conclusion that, for the time being, the transportation of the quetzalapanecáyotl—by air or sea—would be too risky for its fragile feathers. Unintentionally, these twenty-three souvenirs function thus as memory aids and evidence—they continually recall the fact that the quetzalapanecáyotl has not been returned.

Our project strives to move “beyond” these impasses. It started with the following question: How can we think about restitution in relation to processes of repair and regeneration taking other-than-human aspects of existence into account? What’s more, in these times of deep uncertainties, the entire network of ecosystems, which are spiralling out of control, is at stake—the interdependence between humans and their environment in all its manifestations, must be regarded. Rather than debating the necessity or potential risks of physically returning the quetzalapanecáyotl, our collaboration thus embarked from the tangible aspects of the object—specifically, the more than 12,000 feathers used in its fabrication, though now untouchable—to focus on the tangible impact of the souvenirs production. Although across the Atlantic and more than 9,000 kilometres in between, this production has environmental impacts on, for example, the habitats of the birds that provided the object’s feathers—the cotinga, quetzal, roseate spoonbill, and squirrel cuckoo. Hence, we ask: How can these souvenirs serve as acts of gift-giving and self-gifting without causing further harm?

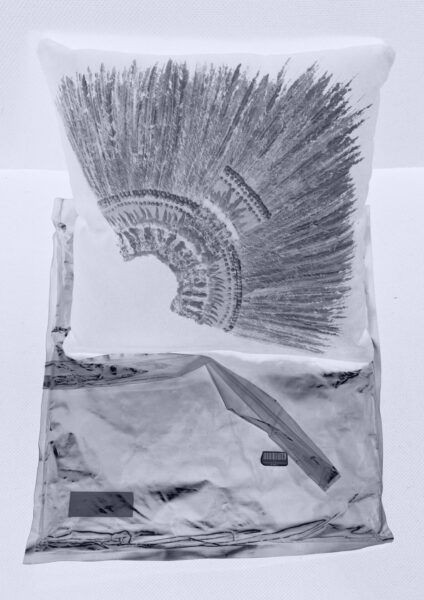

One of the “special topics” listed on the museum’s website for searching souvenirs is “Sustainable.” If you browse for it, you will find only one of the twenty-three souvenirs featuring the quetzalapanecáyotl: a cushion. The description highlights that the cushion is made of microfiber, composed of 100% recycled polyester. For the museum, the concept of “sustainable” appears to be defined solely using recyclable materials. However, we sought to challenge this narrow interpretation of sustainability by evaluating the associated footprints through a broader and more holistic lens—one that incorporates the social, economic, and political dimensions of production. This approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of the product’s true impacts throughout its entire lifecycle, that is, by assessing each stage of its creation, use, and disposal.

We assessed the socio-environmental footprint of a set of museum souvenirs by integrating five indicators —resources, emissions, energy, waste, and human well-being— into a footprint index ranging from 0 (no impact) to 1 (greatest impact). An exhaustive literature review led to the creation of a dataset that included average estimates for each indicator. Two multicriteria decision-making analysis (MCDM) approaches were proposed to integrate the indicators into a footprint index for each souvenir. Both methods deal with finding an optimal or best solution based on multiple conflicting indicators. A programming interface was also designed to enhance the visualization of model outcomes and clarify the decision-making process, thereby facilitating more informed and effective decision-making.[3] This tool allows modifying indicators’ weights according to specific stakeholders’ interests and objectives. Furthermore, the process is designed to be fully transparent and interpretable, enabling a clear understanding of how input parameters are utilized and enhancing the overall explainability of the results which includes an integrated assessment of its footprint.

Our framework of analysis also includes the ability to explore plausible “scenarios” of museum souvenirs, which can be adapted to assess potential footprint impacts under a set of predefined conditions. These scenarios are constructed by adjusting the weights of different indicators, which are then analysed using the multicriteria techniques explained above. Rather than being viewed as definitive predictions of the future, these scenarios serve as tools for collectively exploring how the interests and priorities of various stakeholders may lead to either sustainable or unsustainable outcomes. This approach fosters dialogue, encourages collaboration, and provides insights into how diverse perspectives can shape more responsible and informed decision-making.

For example, our analysis of the cushion’s impacts revealed that it ranks among the top ten products with the highest socio-environmental footprint. This ranking is based on a comprehensive evaluation that considers both environmental and social dimensions, including resource extraction, energy consumption, waste generation, emissions, and the well-being of communities involved in its production and supply chain. The findings highlight the significant impact this product has across various stages of its life cycle, emphasizing the need for sustainable practices and more responsible production methods to mitigate its footprint.

Our framework explicitly considers the political, social, and institutional contexts at both regional and local levels, which influence interactions within networks of actors. From this perspective, integrating the multicriteria techniques —such as those explained above— with collaborative research offers a constructive approach to uncovering the systems that underpin sustainability-related decision-making. This holistic approach deepens the understanding of complex dynamics and supports the development of more informed, context-sensitive strategies for advancing sustainability priorities. In short, decisions made today impact the complex futures ahead on this damaged planet.

The quetzalapanecáyotl souvenirs have the potential to act as a bond where different actors —such as manufacturers of souvenirs, retail managers of museum shops, and purchasers— can recognize shared histories and other-than-human entanglements. The colonial formation of Europe is built upon the exploitation of Mexico’s bodies, ecosystems, cultures, and heritage. The deforestation and extractivism that have plagued Mexico from the sixteenth century to the present day are merely the other side of this colonial process. As a result, the habitats where the quetzal—the most emblematic bird among those whose feathers were used for the quetzalapanecáyotl—once thrived are now nearly destroyed, and the quetzal itself is on the brink of extinction. A holistic approach to restitution, we propose, could involve efforts to restore these ecosystems, not least as part of an attempt to construct an imaginary and a politics that are no longer human-centred. Our project is a small gesture toward this endeavour, processing the pasts for envisioning future scenarios that aim to collectively “think about how much you can give up to promote more life”.[4]

This text presents the final edition of PENACHO VS PENACHO (2011-2025), a long-term project by Nina Hoechtl exploring the Penacho de Moctezuma, known as quetzalapanecáyotl in Nahuatl, and the shifting power dynamics surrounding it. Each edition examines aspects of restitution, imagining the artifact alongside its beyond-human stakeholders.[5]

[1] Kunsthistorisches Museum Shop, accessed December 29, 2024, https://shop.khm.at/en/.

[2] As of August 2025, the enamel pin is no longer available in the museum shop. Kunsthistorisches Museum Shop, “Enamel Pin: Quetzal feathered head,” accessed December 29, 2024, https://shop.khm.at/en.

[3] The app https://eco-footprint.vercel.app/ was developed by Nina Hoechtl, Yosune Miquelajauregui, Raúl de la Rosa, and Camila Toledo Jaime at the National Laboratory of Sustainability Science of the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

[4] Naomi Klein and Leanne Simpson. “Dancing the World into Being: A Conversation with Idle No More’s Leanne Simpso,” Yes! Magazine, March 6, 2013.

[5] PENACHO VS PENACHO (2011-2015): http://www.ninahoechtl.org/works/penacho-vs-penacho-2011-2025/